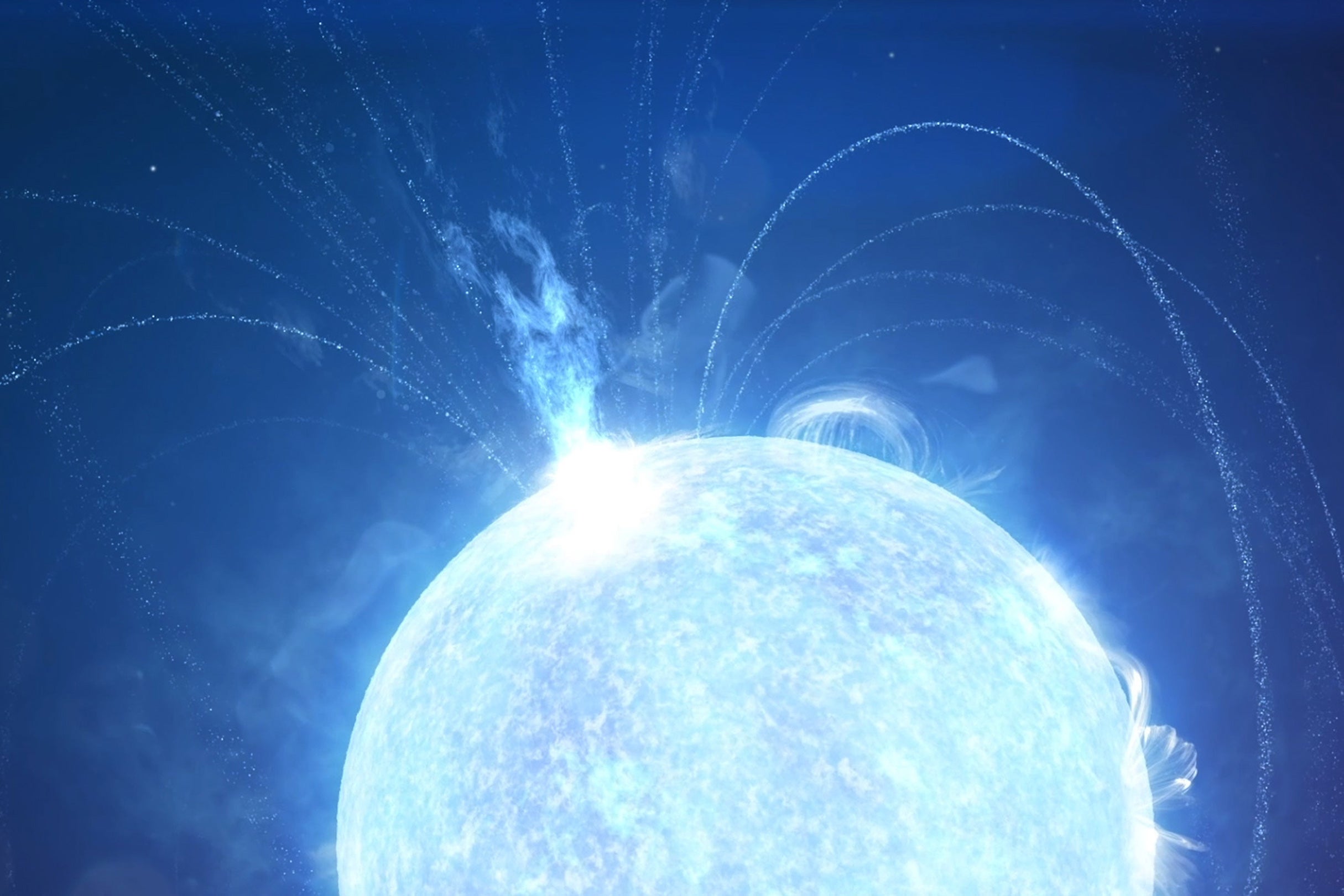

A dense, magnetic star violently erupted and spat out as much energy as a billion suns — and it happened in a fraction of a second, scientists recently reported.

This type of star, known as a magnetar, is a neutron star with an exceptionally strong magnetic field, and magnetars often flare spectacularly and without warning. But even though magnetars can be thousands of times brighter than our sun, their eruptions are so brief and unpredictable that they’re challenging for astrophysicists to find and study.

However, researchers recently managed to catch one of these flares and calculate oscillations in the brightness of a magnetar as it erupted. The scientists found that the distant magnetar released as much energy as our sun produces in 100,000 years, and it did so in just 1/10 of a second, according to a statement translated from Spanish.

A neutron star forms when a massive star collapses at the end of its life. As the star dies in a supernova, protons and electrons in its core are crushed into a compressed solar mass that combines intense gravity with high-speed rotation and powerful magnetic forces, according to NASA. The result, a neutron star, is approximately 1.3 to 2.5 solar masses — one solar mass is the mass of our sun, or about 330,000 Earths — crammed into a sphere measuring just 12 miles (20 kilometers) in diameter.

Matter in neutron stars is so densely packed that an amount the size of a sugar cube would weigh more than 1 billion tons (900 million metric tons), and a neutron star’s gravitational pull is so intense that a passing marshmallow would hit the star’s surface with the force of 1,000 hydrogen bombs, according to NASA.

Magnetars are neutron stars with magnetic fields that are 1,000 times stronger than those of other neutron stars, and they are more powerful than any other magnetic object in the universe. Our sun pales in comparison to these bright, dense stars even when they aren’t erupting, study lead author Alberto J. Castro-Tirado, a research professor with the Institute for Astrophysics of Andalucía at the Spanish Research Council, said in the statement.

“Even in an inactive state, magnetars can be 100,000 times more luminous than our sun,” Castro-Tirado said. “But in the case of the flash that we have studied — GRB2001415 — the energy that was released is equivalent to that which our sun radiates in 100,000 years.”

A “giant flare”

The magnetar that produced the brief eruption is located in the Sculptor Galaxy, a spiral galaxy about 13 million light-years from Earth, and is “a true cosmic monster,” study co-author Victor Reglero, director of UV’s Image Processing Laboratory, said in the statement. The giant flare was detected on April 15, 2020 by the Atmosphere–Space Interactions Monitor (ASIM) instrument on the International Space Station, researchers reported Dec. 22 in the journal Nature.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in the ASIM pipeline detected the flare, enabling the researchers to analyze that brief, violent energy surge; the flare lasted just 0.16 seconds and then the signal decayed so rapidly that it was nearly indistinguishable from background noise in the data. The study authors spent more than a year analyzing ASIM’s two seconds of data collection, dividing the event into four phases based on the magnetar’s energy output, and then measuring variations in the star’s magnetic field caused by the energy pulse when it was at its peak.

It’s almost as if the magnetar decided to broadcast its existence “from its cosmic solitude” by shouting into the void of space with the force “of a billion suns,” Reglero said.

Only about 30 magnetars have been identified from approximately 3,000 known neutron stars, and this is the most distant magnetar flare detected to date. Scientists suspect that eruptions such as this one may be caused by so-called starquakes that disrupt magnetars’ elastic outer layers, and this rare observation could help researchers unravel the stresses that produce magnetars’ energy burps, according to the study.

Copyright 2021 LiveScience, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.