Have you ever wanted to eat breakfast sitting across from a dire wolf or watch a saber-toothed cat roar from the comfort of your living room? These ice age animals have been extinct for more than 10,000 years, but scientists are bringing them back to life—virtually.

The team developed three-dimensional, animated models of some of the ice age animals found in the site of Rancho La Brea, better known as the La Brea Tar Pits, in Los Angeles. Researchers at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum, and the University of Southern California worked with a video game development company to build the models and adapt their work for augmented-reality-enhanced (AR-enhanced) museum exhibits, as well as smartphone-based AR experiences on platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram. The study was published on March 2 in Palaeontologia Electronica.

The team hopes that bringing scientifically accurate models to a broad audience will encourage paleoart to become more rigorous. This genre, which includes paintings, sculptures and other artistic reconstructions of prehistoric life, is based on scientific evidence but can be error-prone. “Paleoart is a hypothesis about an extinct animal,” says study co-author Matt Davis, a paleontologist and exhibition developer at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “The problem is that we don’t treat paleoart with the same rigor that we treat our other scientific research.” Co-author Emily Lindsey, a paleontologist and excavation site director at the La Brea Tar Pits, agrees. She describes paleoart as “this very cool, imaginative space that overlaps with science. But it’s almost never the case that the artists are overtly justifying their scientific choices.”

As an example, Lindsey cites the sculpture of a Columbian mammoth sinking into the Lake Pit outside the La Brea Tar Pits Museum—a portrayal that could perpetuate the misconception that asphalt pools were like quicksand. They were actually only a few centimeters deep, so animals were caught in them like a fly caught on a sticky trap, not one drowning in a jar of honey. “That is the most iconic image of the La Brea Tar Pits, and it’s been propagated thousands of times in popular culture,” Lindsey says.

The team initially set out to study how much augmented reality can enhance museum visitors’ engagement. “People are pitching new technology in museums all the time,” Davis says, “but there’s actually very little research that shows that people learn better in AR.” To put this tech to the test, the scientists decided to implement multiple AR-enhanced exhibits at the Tar Pits Museum. The exhibits would feature some of the hundreds of plants and animals whose fossils have been discovered at the tar pits over the past century or so. After running a small but promising AR pilot study, the researchers looked for more accurate AR assets for a larger study and hit an immediate snag: peer-reviewed, scientifically accurate AR models of ice age flora and fauna did not exist, Lindsey says. So they decided to make their own.

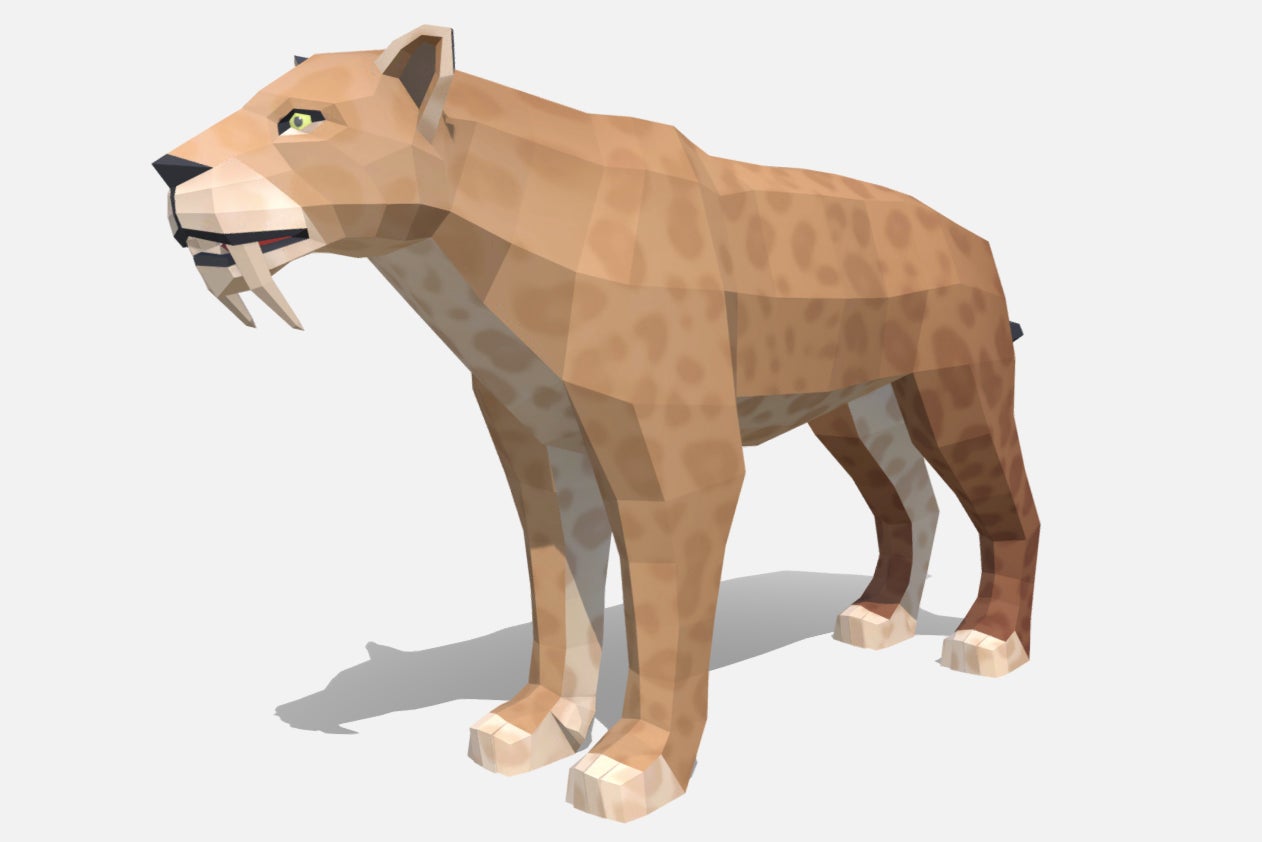

The researchers re-created 13 popular ice age animals—including a dire wolf, saber-toothed cat, American lion and Columbian mammoth—using low-polygon, or “low-poly,” graphics. A low-poly graphic is built from polygons, two-dimensional, typically triangular shapes that are merged together to form a 3-D figure.

Low-polygon, or low-poly, model of a western horse. Credit: “Designing Scientifically-Grounded Paleoart for Augmented Reality at La Brea Tar Pits,” by Matt Davis et al., in Palaeontologia Electronica, Article No. 25.1.a9. Published online March 2022 (CC BY 4.0)

Despite its blocky appearance, this style gives the models a few advantages. Low-poly graphics originated in the early days of 3-D animation, when computer processing power was a shadow of what it is today. Because they require little such power, they are easy for a modern computer or smartphone to render. And thanks to their long history of being used in video games, low-poly graphics have become a publicly accepted animation style, says U.S.C. computer scientist and study co-author Bill Swartout.

Because low-poly graphics are inherently more abstract, they also cut down the paleoart inaccuracies that arise when artists try to create something more photorealistic. In those situations, reconstructors must make uninformed guesses about things fossils rarely tell us, such as the texture or intricate patterning of fur. “What is novel about this approach is that it allows us to not overcommit on the details,” Swartout says.

Instead of guessing at unknowns, the team focused on incorporating the most up-to-date paleontological findings about how these ice age animals looked and behaved. “We asked, ‘What’s the latest science on how giant sloths walked or what sound dire wolves might have made or how many humps a western camel would have had?’” Lindsey says.

“Low-poly model of a Harlan’s ground sloth. Credit: “Designing Scientifically-Grounded Paleoart for Augmented Reality at La Brea Tar Pits,” by Matt Davis et al., in Palaeontologia Electronica, Article No. 25.1.a9. Published online March 2022 (CC BY 4.0)

“Paleoart can definitely spark curiosity,” says Mariah Green, museum and collections manager at Virginia Tech’s Museum of Geosciences, who was not involved in the study. “But it’s important to be accurate, because it can communicate new scientific information about discoveries in the fossil record.”

The researchers are now using their models in AR-enhanced exhibits and continuing to gather and analyze data on how this technology impacts museum visitors’ engagement and learning. They are still early in this process—those exhibits are not yet open to the full public—but according to Davis, AR is looking like a promising supplement to existing techniques, as opposed to a replacement for traditional learning tools.

The team has also made its models available on social media so people can explore the animals at home. Co-author Ben Nye, director of learning sciences at U.S.C., sees the value of AR outside of a museum context. “I think that, ultimately, augmented reality is going to be a very impactful learning technology because you’re adding things to the real world,” he says. “It enables people to see themselves in other physical and social contexts.” For instance, using Snapchat to drop a dire wolf into your living room could demonstrate its size and strength much more powerfully than a description in a textbook could.

Davis hopes this study helps set a new scientific standard for all paleoart from physical illustrations and sculptures to digital models. “We’re putting all of our research out there,” he says. “We want people to be able to say, ‘Hey, this is why this thing looks the way it does, and I can now make another model that’s even more accurate.’”

As Green puts it, this is “all about transparency at the end of the day.”