Deep under the ice of Antarctica’s Ekström Ice Shelf there is nothing but complete darkness.

Well, complete darkness and a thriving ecosystem that’s existed for thousands of years, according to a new paper by researchers from the UK and Germany.

“This discovery of so much life living in these extreme conditions is a complete surprise and reminds us how Antarctic marine life is so unique and special,” says lead author and British Antarctic Survey marine biologist, David Barnes.

“It’s amazing that we found evidence of so many animal types, most feed on micro-algae (phytoplankton) yet no plants or algae can live in this environment. So, the big question is how do these animals survive and flourish here?”

The researchers used hot water (we kid you not) to drill two boreholes on the relatively small Ekström Ice Shelf in East Antarctica back in 2018. One hole went down 192 meters (630 feet) of ice until it hit 58 meters of liquid water, while the other spanned 190 meters of ice with 110 meters of water underneath.

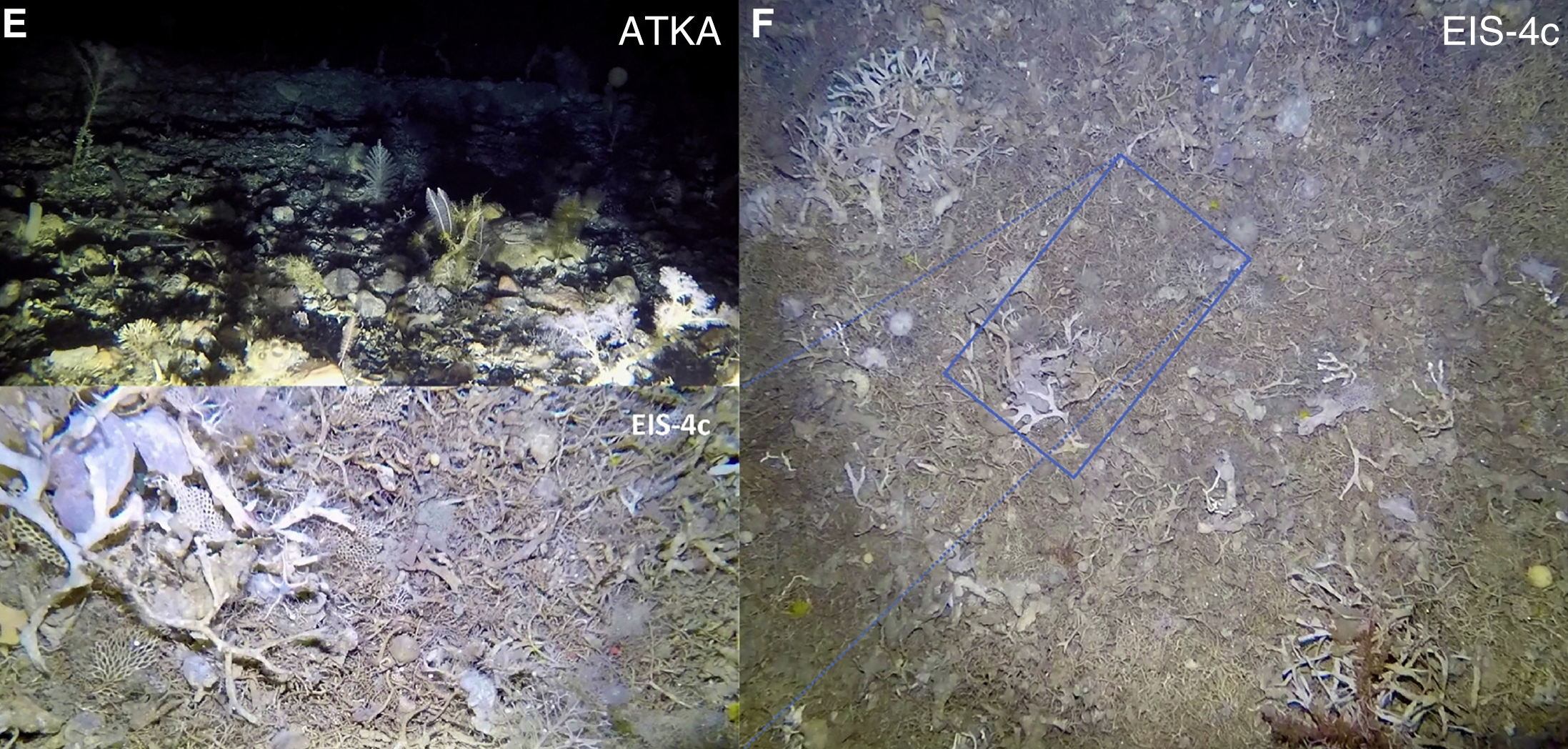

What they found in that dark, cold and food-scarce place under the ice was life, and lots of it. The team discovered 77 species from 49 different genera bryozoans, including sabre-shaped Melicerita obliqua, and serpulid worms such as Paralaeospira sicula.

Fragments of bryozoans discovered on the seabed. (David Barnes)

Fragments of bryozoans discovered on the seabed. (David Barnes)

All of these creatures are suspension feeders – they sit in one place and, with feathery tentacles, snatch particles of organic matter from the water as it flows around them – which means that some kind of food source like sunlight-dependent algae must be getting in under the ice sheet.

This is pretty surprising, considering the closest open water source is 9.6 kilometers (6 miles) away. And past research has found life even further inland on bigger ice sheets like the Ross and McMurdo Ice Shelves.

“Despite permanent darkness for at least thousands of years, life has been observed even 700 km from ice shelf edges,” the team writes in their paper.

“It was thought that richness and abundance of life under ice shelves is highly depauperate. Yet, the biodiversity we found at both borehole sites would be high even for open-marine Antarctic continental shelf samples.”

Fragments of four species of Cellarinella even showed growth increments, similar to a tree’s rings, and the researchers discovered they were similar to other sized growth increments from samples around Antarctica.

Benthic assemblages at two of the study sites. (Barnes et al., Curr Bio, 2021)

Benthic assemblages at two of the study sites. (Barnes et al., Curr Bio, 2021)

But the researchers didn’t just find today’s filter feeders deep under the ice; they also looked at long-dead fragments and carbon dated them to discover their age.

“Another surprise was to find out how long life has existed here. Carbon dating of dead fragments of these seafloor animals varied from current to 5,800 years,” says one of the researchers, Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research geologist Gerhard Kuhn.

“So, despite living 3-9 km from the nearest open water, an oasis of life may have existed continuously for nearly 6,000 years under the ice shelf. Only samples from the sea floor beneath the floating ice shelf will tell us stories from its past history.”

This brings up another problem – in glacial events of the past when most of the Antarctic shelf was overridden by grounded ice (ice that reaches all the way to the sea floor), how did these dark ecosystems survive?

The new information suggests that the creatures lived in small areas that were not grounded, while open areas of water surrounded by sea ice would have allowed phytoplankton to thrive and then get eaten by those creatures far under the ice. The plankton would have been swept under the ice by the flow of the water – within the reach of the hungry creatures far beneath.

Unfortunately, despite the incredibly long life of these ecosystems so far, the researchers are nervous about their future.

“It may be cold, dark and food-scarce in most places,” the team writes, “but the least disturbed habitat on Earth could be the first habitat to go extinct as sub-ice shelf conditions disappear due to global warming.”

The research has been published in Current Biology.