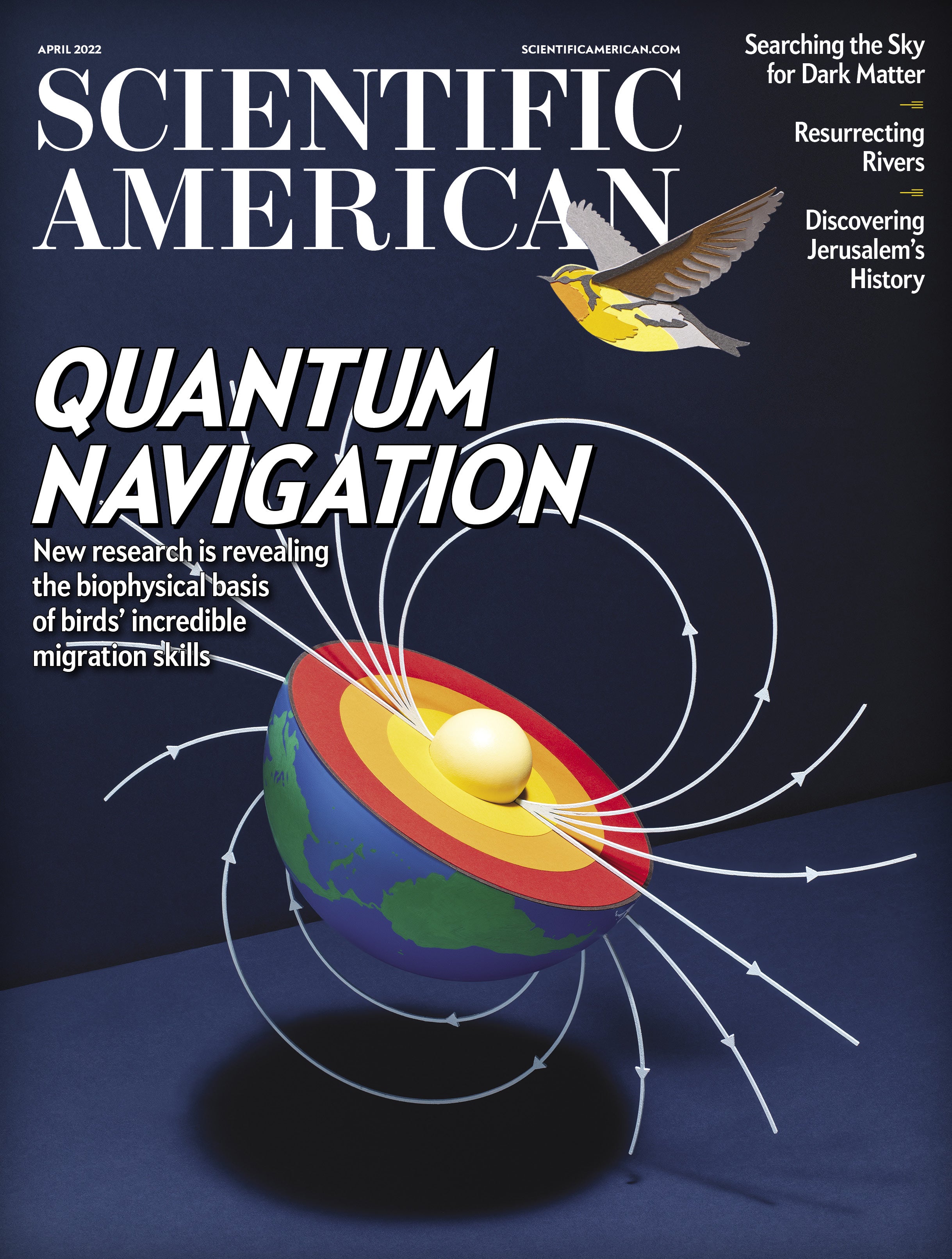

While we sleep this spring, billions of birds will be flying through the night from their wintering grounds to their breeding territories. Bird migration is a mind-bendingly astonishing phenomenon: these tiny creatures fly thousands of kilometers with enough precision to return to the same nesting site year after year. They use three types of compass, guided by the stars, sun and, most mysteriously, Earth’s magnetic field. In this issue’s cover story, scientists Peter J. Hore and Henrik Mouritsen explain how some birds are able to “see” Earth’s magnetic field using quantum effects in exquisitely photosensitive molecules in their eyes. We hope this article will add to the enjoyment of seeing migratory birds return to your neighborhoods after a long winter.

I’ve been looking at streams with more appreciation after reading about their “hyporheic zone,” the area of streambed extending below the water and to the sides of a waterway. This hidden layer of sand and gravel, where the groundwater and stream mix, is home to small animals and larvae and microbes. As author Erica Gies describes, it’s known as the “liver of the river” because of how it keeps a waterway healthy. People who are restoring drained or dying streams are using new knowledge about the hyporheic zone to bring back thriving habitats.

Looking up from streams and beyond the birds, astronomers are planning ambitious projects to seek the source of dark matter, the invisible stuff in the universe that moves stars and galaxies. Theoretical physicist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein presents the best ideas for how to look for dark matter, some of which could get a boost this year if physicists involved in a once-a-decade planning project endorse dark matter probes as a top scientific priority. (We hope they do.)

The culture of astronomy has been transformed by a wave of women entering the field (including Scientific American advisory board member Meg Urry), as writer Ann Finkbeiner observes. She is admired in science writing circles for inspiring the “Finkbeiner test,” a guide to avoiding sexist clichés when talking about women in science. Now she realizes we are in a new era, when women are proudly themselves and determined to make science more welcoming to all.

Biblical archaeology is another field being transformed, albeit fitfully. Researchers using modern analytical methods are trying to add some rigor to excavations in Jerusalem, which have been guided by scripture rather than science. Author Andrew Lawler shows how religious and international conflicts add to physical constraints (the land is very crumbly) to make this one of the most challenging places in the world to unearth true history.

Modern neuroscience began with Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s careful observations of neurons and how they interact. Author Benjamin Ehrlich details how revolutionary Cajal’s ideas were and how they changed the way we think about the brain. The painstakingly drawn illustrations are indeed wondrous.

In 1889 Scientific American shared some of Thomas Edison’s thoughts on sleep. He was against it. But he did appreciate napping—or at least the half-asleep state that led to many of his inspirations. Starting here, you can learn how to follow his advice to extract creativity from a snooze. Writer Bret Stetka tells the tale.

We’re introducing a print column this month called Mind Matters, in which experts will share recent interesting insights from social science. Enjoy, and let us know what you think.