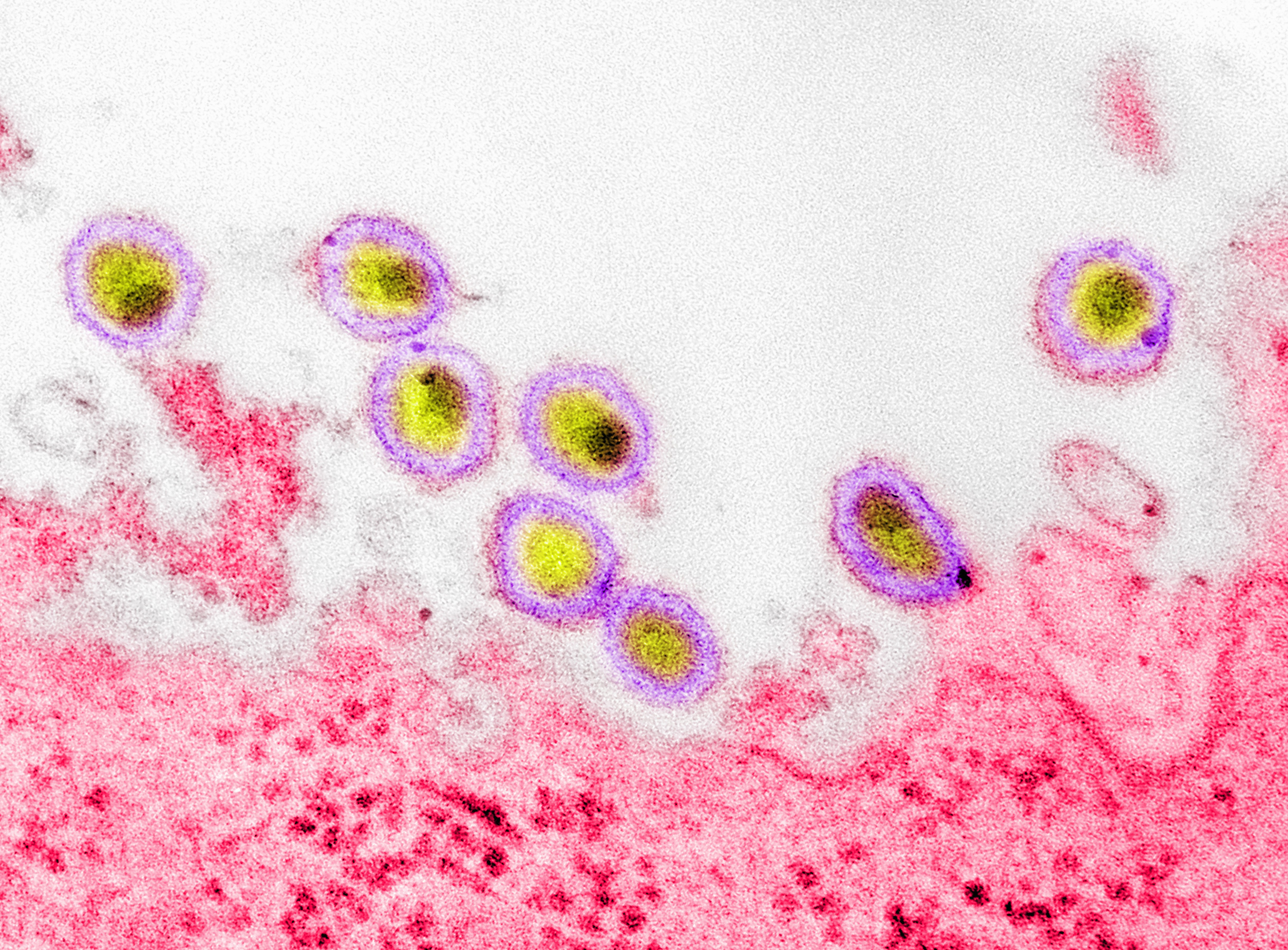

As SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, has spread throughout the world, many observers have failed to take note of the millions of illnesses and deaths caused by HIV—another virus that has approached pandemic status during its history. Now an HIV variant that is more virulent and transmissible has been discovered in the Netherlands, where it apparently has been circulating for decades, according to new research. Luckily, none of the variant’s new mutations make it resistant to widely used therapies. But the finding may offer a warning for how the COVID pandemic could proceed in the coming months: viruses do not necessarily evolve to become milder.

Without treatment, people infected with the newly identified HIV variant have more than three to more than five times higher levels of the virus in their blood, making them more infectious. Plus, their immune system deteriorates twice as fast, setting them on a course to potentially develop AIDS years earlier than people with other versions of HIV. These findings, published this month in Science, indicate the newfound variant carries more than 500 mutations scattered across its genome—though it is unclear how they enable the virus to cause more-severe disease.

William A. Haseltine, an infectious disease researcher who founded Harvard University’s cancer and HIV/AIDS research departments and now chairs the think tank ACCESS Health International, has written extensively about the potential of SARS-CoV-2 assume a more dangerous form. Haseltine spoke with Scientific American about why a more virulent variant of HIV—a virus that has been known for nearly half a century—is just coming into focus now, whereas the new coronavirus has spawned several “variants of concern” in a matter of months.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

What does the discovery of a more virulent HIV variant tell us about how viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, evolve?

We’ve known that all viruses adapt. The way they adapt is much like how we use artificial intelligence to solve complex problems: the machine throws a lot of random combinations at something, and the one that works best is the one that survives.

With HIV, [its evolution has] been a long, drawn-out process because the virus is poorly transmissible. It takes, on average, 100 sexual contacts for a man to give it to a woman and 200 contacts for a woman to give it to a man. The process is a slower-evolving one—not because the virus doesn’t change but because the replication cycles can be quite long. For Omicron, those cycles can take hours or days at the most. The virus can be transmitted by a person simply breathing the air somebody else breathed a half an hour ago.

In the past year or so, SARS-CoV-2 has produced several different variants of concern. How worried should we be that more virulent versions of the virus are yet to emerge?

First of all, the virulence of SARS-CoV-2 has been very stable—with the exception of Delta, which is twice as likely to land you in the hospital. Delta was a warning shot across our bow, showing the virus can become both more transmissible and more virulent. There is nothing that we know of that restrains this virus from becoming as lethal as its cousin SARS-CoV-1. We still have no clue whether one genetic change or many make SARS-CoV-1 so much more virulent than SARS-CoV-2. As long as we are in the dark about what it is that determines the virulence of the virus, we have no idea which direction the next variant will come from. So I’ve been telling policy makers to be optimistic about the upside but prepare for the downside.

Are some viruses poised to produce more variants of concern than others?

Yes, RNA viruses [such as HIV and SARS-CoV-2], in general, make more mistakes [and thus enable more opportunities for evolution] than DNA viruses. Your cells have elaborate machinery to fix mistakes in DNA, which must last a long time to be inherited, whereas RNA is effervescent and plays a more transient role in cellular life. It turns out that SARS-CoV-2 has a proofreading enzyme that can correct mistakes, so people thought that would protect against variation. They were incorrect. One of the major errors people made in underestimating this virus was the extent to which it can change.

HIV and SARS-CoV-2 are both RNA viruses. Do the factors driving their evolution differ, and if so, how?

The selective pressure on a virus is to survive, just like it is for any other organism. What the virus wants to do is get from one person to another—get in and get out. Because HIV is so poorly transmitted, its best strategy is to get in and stay there for a very long time and rely on a predictable behavior—sex—to get out.

For SARS-CoV-2, the virus depends for its existence on reinfecting people who have been infected the year before. We are fighting millions of years of evolution of an organism that knows how to fool our immune system and get into us again and again. One thing we have seen the viral variants doing is getting faster and faster [at transmission]. Delta is faster than Alpha. Omicron is faster than Delta. And BA.2 Omicron is faster than BA.1 Omicron. There are many ways for this virus to mutate to increase its transmissibility. Whether any of those will affect virulence is unclear.