Ashleigh Papp: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science, I’m Ashleigh Papp.

Monogamy in animals…and let’s be honest, in humans too…is a funny thing. Only a few animal species have been lumped into the one-partner-for-life category, and even then, there are exceptions to those rules.

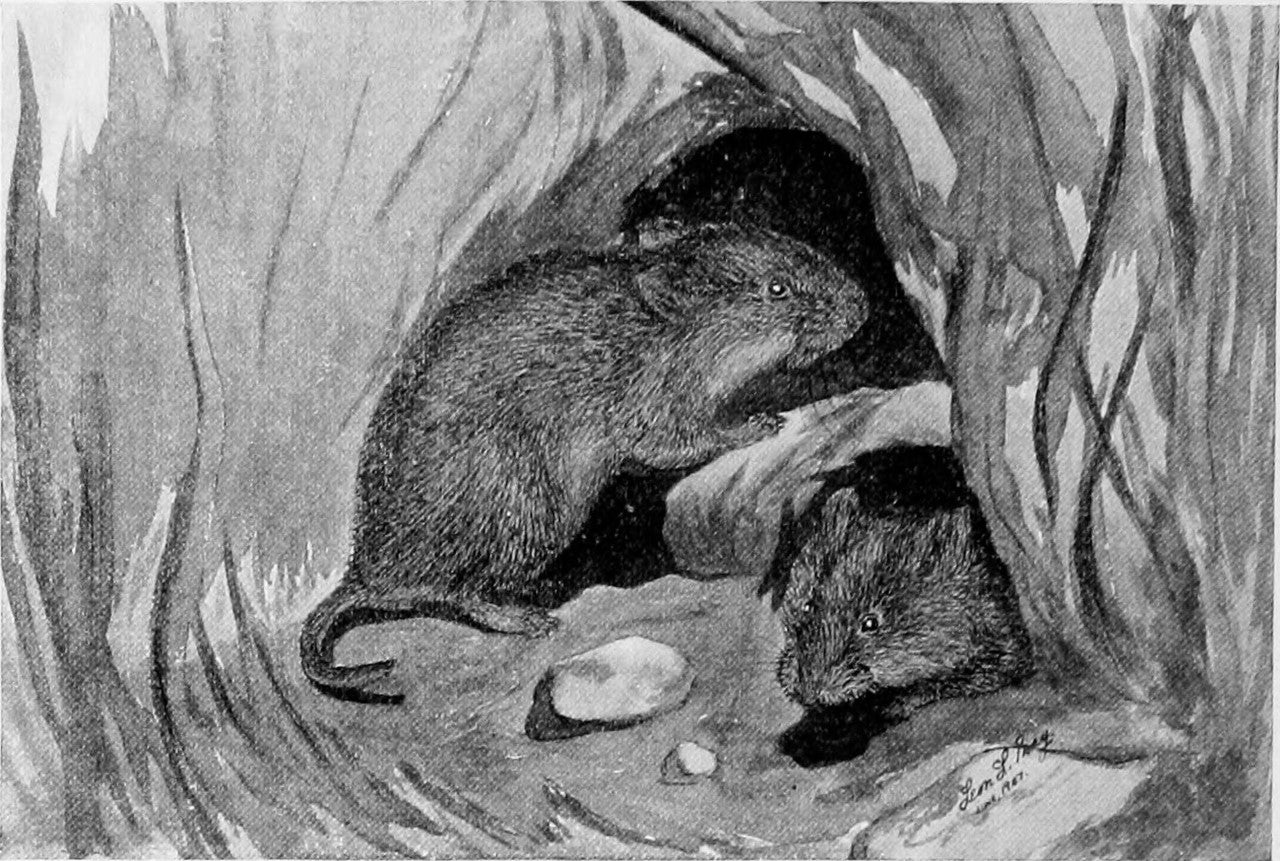

Prairie voles are furry little rodents that live throughout North America. They’re a particularly interesting species because they form lifelong partnerships. Annaliese Beery, a behavioral neuroscientist with Smith College in Massachusetts and the University of California at Berkeley, studies vole monogamy in the wild and in the lab.

Annaliese Beery: So I would define monogamy as a formation of a lasting partnership or a social relationship between mates. Social relationships are very important for human biology and prairie voles are one of the only species that are studied in the lab that exhibit this trait. Monogamy is fairly rare in rodents, and it’s also unusual for rodents to form lasting social relationships of any kind.

Papp: We already know about some things that support monogamy in the wild—like when mates are scarce and it makes sense to hold onto the one you’re with, or when both sexes stick around to raise their young. But so far, there isn’t one clear explanation as to why or how animals opt for only one partner.

Whatever the reasons, staying monogamous requires effort from both sides. To better understand how lifelong bonding works, Beery and her team wanted to know if both male and female prairie voles make equal investments in making the long haul work.

To find out, the researchers set up an experiment with three phases. In the first phase, they had to teach the prairie voles how to open a door controlled by a lever.

Beery: It was actually really hard to get prairie voles to press a lever for a reward. And we had some voles who never learned the task, and they were not included in the study. We had other voles who learned to press the lever in non-typical ways, one female liked to sit on the lever in order to activate it. And then one day, something clicked and she turned around and started pressing it with her paw and getting the food pellet in the ordinary way.

Papp: The team built on that skill by associating the lever pressing with a door opening.

In phase two, there were two doors, controlled by two different levers. One of the doors led to a cushy rodent pad complete with wood shavings, fresh produce and even Cheerios, while the other led to a shallow pool of water. (Just FYI, these rodents really aren’t into swimming pools.)

The voles could distinguish between two doors, two levers, and two different outcomes. And ultimately, both the males and females overwhelmingly pressed the lever that took them into the cushy chamber over the water torture.

In phase 3, they took a quick break from the lever pressing and introduced each vole to a member of the opposite sex. The two voles got 48 hours to bond and grow fond…and then the lever pressing resumed.

Each of the trained voles were given the option of two levers and two doors again. But this time, one of the doors led to their partner and the other led to a new member of the opposite sex.

After all of the little vole-sized levers were pulled, Beery and her team analyzed the results. They found that even when it comes to monogamous prairie voles…males and females sometimes have different priorities.

Beery: So females worked hardest to get to familiar male mates versus unfamiliar strangers. The males were interesting because they showed diverse behaviors, some of them acted like the females and worked hardest to get to their mates consistently over the course of the study. Other males consistently worked hardest to get to unfamiliar females, and yet other males were sort of intermediate where they would press more for a familiar female on one day and an unfamiliar female on the next day.

Papp: Their results were published in the journal Genes, Brain and Behavior. [Annaliese K. Beery, et al., Sex differences in the reward value of familiar mates in prairie voles]

Overall, this points to a big difference between the sexes when it comes to social motivation. In other experiments, vole researchers have observed “wandering,” or a preference by males for the unfamiliar females. But many of those studies were performed out in the wild, and this research removed those external pressures. That seems to mean that some of these little males were sometimes flighty about staying true to their mate because, well, maybe they felt like it.

According to Beery, putting vole monogamy to the test helps us better understand the different types of human relationships and our process for selecting who we spend time with.

For prairie voles, the investment seems a bit skewed to the female side, but no need to throw shade on the males, Beery says, there’s likely a legit explanation out there. And while science looks for that reason—maybe don’t give up on finding your one true love quite yet.

For Scientific American’s 60-Second Science, I’m Ashleigh Papp.